King, M, Timms, P & Mountney, S. (2022) A proposed universal definition of a Digital Product Passport Ecosystem (DPPE): Worldviews, discrete capabilities, stakeholder requirements and concerns, Journal of Cleaner Production, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135538

Read article …

Category: Data Innovations – Product Passports

Our Response to the UK’s Net Zero Review

The UK Government’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy recently held a call for evidence as part of its Net Zero Review; an independent review of the government’s approach to delivering its net zero targets. On the back of our Product Passport Innovations Project, and as Systems Engineers, we felt we could make a valuable contribution to this consultation, reflecting on our experience in this area and raising awareness of the systems discipline as a way of leveraging the maximum benefit for the most stakeholders. In our response we made four key points:

Complex problems require systems thinking approaches

Delivering Net Zero is complex and requires holistic stewardship. People and organisations must carefully shape and monitor change to avoid undesirable and unintended consequences. Systems thinking approaches are designed to do just this! The UK government is starting to adopt these types of approach, but care must be taken. The government’s policy-making role is to break the broad problem of sustainability into smaller and more manageable chunks that different sectors can solve. But these are still problem statements, not ‘solutions’ to sustainability. Why is this important? Because it changes how government interacts and interfaces with its stakeholders.

Insights from our recent research: incentives and barriers for business

Product Passports are mechanisms that contain information on the sustainability aspects of products and services, providing greater traceability and transparency across the product life cycle, to influence consumer and business behaviors. The EU sees passports as a regulatory innovation; a ‘solution’ where circularity and sustainability is improved by the mandatory requirement to publish and make available certain data through common product passport interfaces. But the EU is taking a wholly solution-focused approach, setting out their vision for an information platform, and specific information points to be shared across that platform, without rationale for the chosen data points. In short, they have jumped from big-picture problem to final detailed solution without exploration of the levels of abstraction in between. Only recently have they acknowledged that information must be purpose-driven. This could have been avoided if a clear systems engineering process had been followed. We hope that UK policy-making learns from these mistakes.

Widespread adoption of systems engineering within and outside of engineering disciplines

Systems Engineering is fundamental in the delivery of whole-life-cycle issues, such as those of net zero, and is time-tested in domains including healthcare, transportation, and the military. To maximize the benefits of any chosen Net Zero intervention, innovation, or technology-facilitated change, the UK government should promote, deploy, and encourage adoption of appropriate systems engineering tools by all stakeholders, to ensure the purpose of such interventions is not lost. The UK government should also avoid ‘solutionizing’ in the specification of technology and data needs, recognizing the patterns that deliver systems without tailoring those systems for a specific purpose (and thus enabling greater flexibility). Finally, the UK Government should avoid the duplication of effort, and systems existing in isolation. Integrate with existing systems and operations, rather than add additional burden. Understand ‘systems of systems’, and how to architect and integrate multiple constituent systems, that are operationally and managerially independent, together to deliver new unique capabilities that no individual system can deliver by itself.

Focus on leveraging ‘the right’ data, not big data

As information becomes increasingly digital, the ability to use data for net zero objectives greatly increases. However approaches based on “we have this data already – what can we do with it?” and “let’s collect all the data we can in case it becomes useful” is not efficient in the pursuit for big impact, fundamental change. A top-down, holistic approach is needed, that can justify why data is needed and when it can and cannot be used (what benefits it will deliver). Systems Engineering provides the cross-disciplinary basis by which such trade-offs can be managed, while systems of systems thinking can help governments better direct their interventions to maximize the benefits they desire.

To read our full response, please see below.

Insights (3): The EU timeline for information in the Battery Passport

Insights post – Part 3 of 3.

The information in this post is now superceded.

NOTE – this blog post relates to a 2023 reserach project which was analysing the evolving EU Batteries Regulation.

In Part 2 of our Insights post, we introduced the specific information points that the EU expects to be accessible within the Battery Passport.

In this video, we explain the timeline, by which these information points should be accessible via the Smart Label, Battery Passport, and Electronic Exchange System Portals.

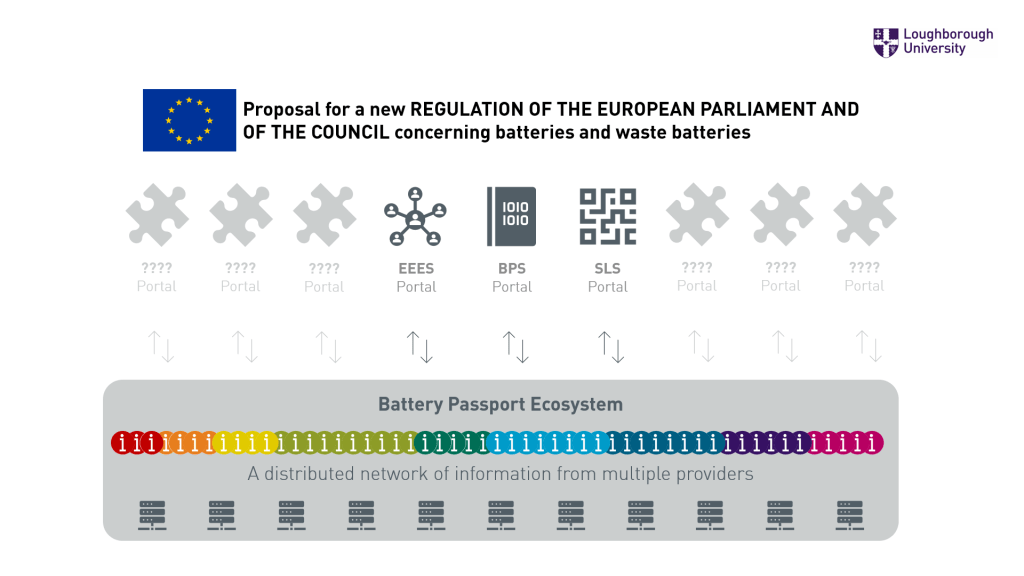

In short: The QR label requirements come first, and are applicable to all types of battery. For industrial and EV batteries, further performance information must be provided via the passport. The Electronic Exchange then requires duplicate access to much of this information. This video ends in an observation; that while the EU explicitly defines three information exchange systems, there are many other forms of information exchange required by the regulation that could also form part of the Battery Passport Ecosystem.

This will be the subject of our next insights article.

Insights (2): Explicit Information Requirements for the EU’s Battery Passport

Insights Post – Part 2 of 3.

The information in this post is now superceded.

NOTE – this blog post relates to a 2023 reserach project which was analysing the evolving EU Batteries Regulation.

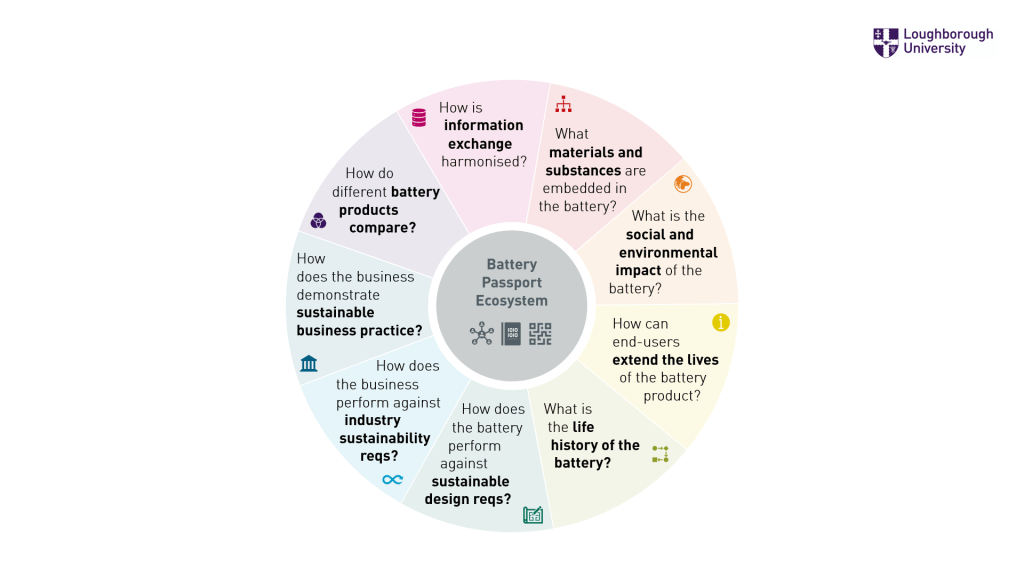

In Part 1of our series of insights post, we provided a basic overview of the EU’s new Battery Regulations and what this meant for the idea of a product passport ecosystem, finishing on a set of nine questions that characterise the information sought by the EU.

In this second video, we cover the explicit information requirements of the EU’s battery regulation mapped on to the nine key functions of a battery passport ecosystem, as identified from our research.

Part 3 of our insights posts goes on to describe the timeline by which these information points should be accessible.

Insights (1): Battery Passports and the EU’s new Battery Regulations

Insights Post – Part 1 of 3.

The information in this post is now superceded.

NOTE – this blog post relates to a 2023 reserach project which was analysing the evolving EU Batteries Regulation.

The EU’s new Battery Regulations are nearly here, and will introduce the first mandatory adoption of product passport technologies.

In this first video, we introduce the EU’s battery regulation and explain it in the context of a ‘Battery Passport Ecosystem’ that we have generated as part of our research.

In short: Battery passports are an information sharing tool designed to improve know-how within the battery value chain, and its overall capability. But their benefits are largely dependent on the information that ends up inside each passport. In the EU’s new battery regulation, three new information innovations are introduced; an Electronic Exchange System, a Battery Passport, and a QR Smart Label. These are being introduced to encourage (and enforce) information transfer between stakeholders. The EU positions these as separate ‘systems’ within the regulation, but information requirements overlap, so really these should be seen as part of a wider battery passport ecosystem, seeking to address nine common questions.

In Part 2, we will explain these nine functional viewpoints of a battery passport ecosystem in more detail, and will identify the explicit and implicit information requirements introduced by the new battery regulations. In Part 3 we will show the timeline by which these information points should be accessible.

Get involved in the DPP Project

We are developing a proof-of-concept technical demonstrator (and data model) for a UK Battery Passport System (Digital Product Passport) for EV and E-Mobility Batteries.

We need your input in our research so that:

- All stakeholders in a circular battery lifecycle can benefit from a standards-based open and / or interoperable record.

- The battery passport proposal enhances opportunities for data innovations during first life applications and supports second-life applications and business models.

- The proposal does not duplicate regulatory or compliance related processes; we want this system to make these processes easier!

- The passport system is accessible and contains the information required for a variety of end-of-life applications.

- The system can help to trace and monitor critical raw materials within the UK economy for urban mining applications

- … and much more!

Please get in touch with Dr Melanie King (m.r.n.king@lboro.ac.uk) and Dr Sara Mountney (s.mountney@shu.ac.uk) to find out more about the project and have your say. In the coming months, we hope to engage with a range of stakeholders to support a collaborative design and development approach to building a technical proof of concept.

Whether you can offer 5 minutes or a few hours, we’d love to get your input into our research!

For more information about the research project, visit our Project Home Page.

Why Digital Product Passports for EV and E-Mobility Batteries?

Focusing on data innovation opportunities for Battery Passports for second-life applications

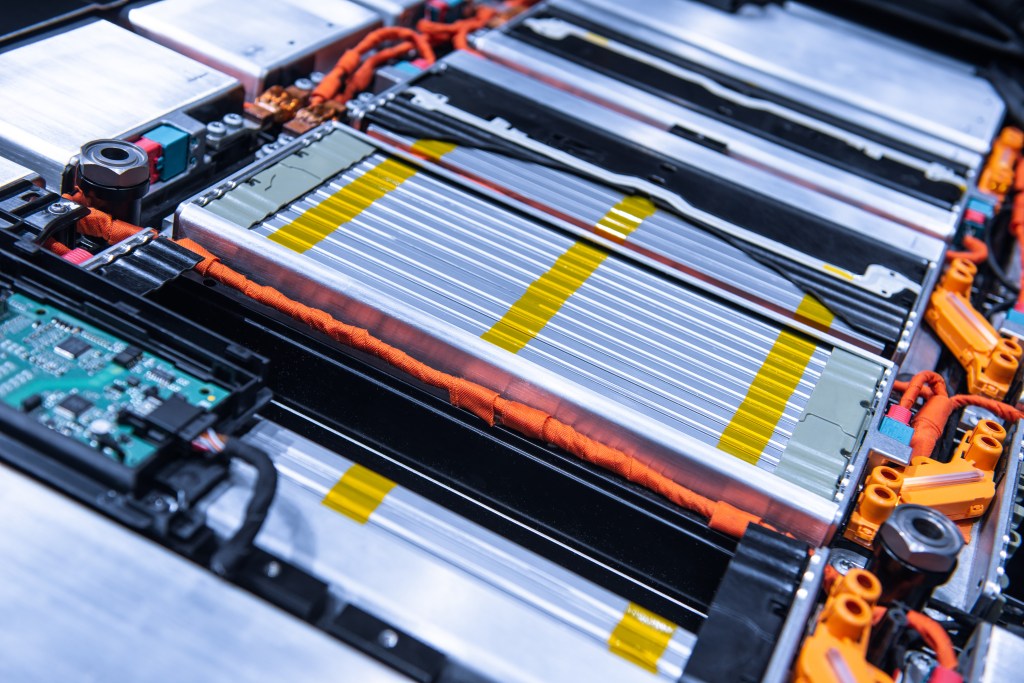

Batteries are manufactured from (predominantly) finite material resources. To ensure the continued availability of critical raw materials, circular lifecycle strategies must be adopted, that manage the flow and availability of the battery product and its constituent parts and materials. High-quality data is required, that can support production, use, re-use, second life, and end-of-life decision-making across the battery value chain.

Proposed by both the UK and the EU, battery passports/product passports are positioned as the mechanism for effective information exchange; a unique electronic record for each manufactured battery that contains all the information necessary to maximise extracted value from materials, and ensure the ongoing availability of those materials for future use. Both the UK and the EU have started to define the types of product information that should be captured by product passports, but the current approach tends to focus on the outputs of a single enterprise – considering battery production and use as a wholly-linear activity. However, battery value chains are complex, networked arrangements of organisations and activities, with multiple re-use, second-life, and end-of-life circularity loops. Each of these loops can also be understood at multiple levels (e.g. re-use, second-life and end-of-life of the battery, re-use, second-life and end-of-life of battery components, and the re-use, second-life, and end-of-life of materials within the battery).

Adopting a system of systems approach, our research seeks to develop a proof of concept and technical demonstrator for an interoperable digital passport information system for the UK, one that addresses this inherent complexity and supports re-use, second life, and end-of-life applications across the value chain. Different loops enable different types of sustainable business models, enabled by different types of information.

We’d like to consult with stakeholders from across the battery lifecycle to understand the viability of these different circularity models, and the information you need (or already have) to make these loops a reality. Putting the multi-stakeholder concept at the forefront of the concept design and development, we hope to identify the challenges and solutions of multiple, interlinked DPPs, that hitherto have not been addressed or considered fully within product passport proposals.

Please email me, Dr Melanie King, to have your say.

Product Passports Project – Aims and Objectives

One of the key challenges identified in the first round of UKMSN+ studies are related to the development of information sharing platforms that enable and support industrial symbiosis. However, in Feb’21 the UK Government put the National Materials Database (NMDHub) project on hold but it re-iterated support for their Product Passport vision, in order to identify the quantity and type of critical raw materials within a given product, and introduce labelling and information requirements as part of the Environment Bill, for example; repairability rating, common faults and remedies, spare parts, instructions for common repairs and upgrades etc.

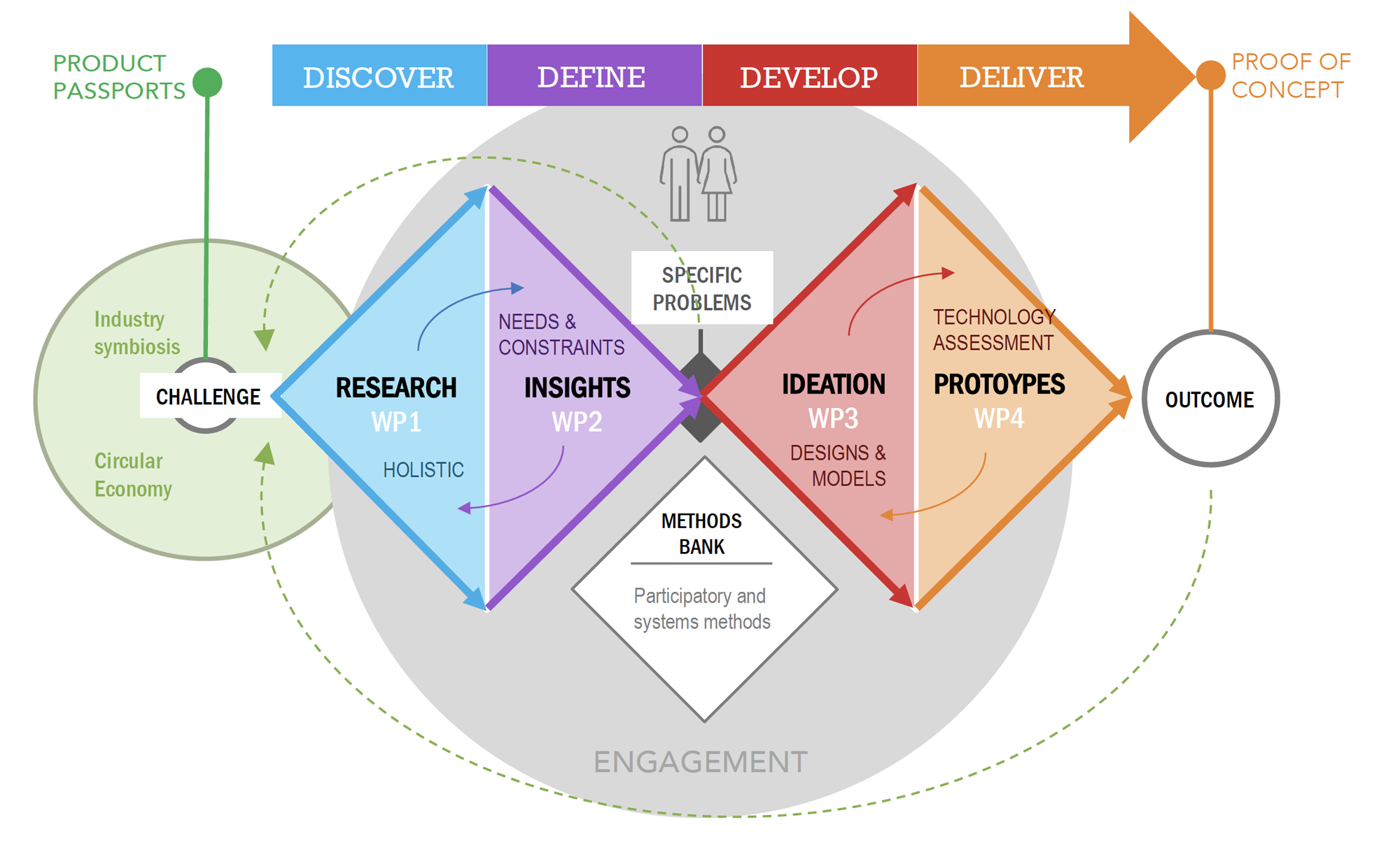

The aim of this 16 month feasibility project is to generate and test new concepts for product passports in order to contribute significantly to the national effort by developing and evaluating a technical demonstrator of a concept for a product passport system and a data publishing specification. The government recognises the need to take a ‘whole-systems’ approach and it is this context this project proposal has been conceived.

Our research project aims to answer the following questions:

- How viable is the notion of a product passport for resource identification and exchange, from a whole systems perspective, and what technologies, data model and distributed architecture might underpin its use to enable cross-industry utility?

- Which concepts of operation for product passports, are most feasible in the context of enabling new business models, ecosystems and circular economy capability?

- What circular economy (holistic) insights could product passports enable with extended capability e.g. data innovations and data-enabled infrastructures like Data trusts, distributed ledger, AI, and connected/smart technologies?

Project Approach

The project will utilise participatory research and collaborative design and development approaches as much as possible, including Systems Thinking and Hackathon style workshops. Our project is different because it aims to break down silos, apply data-driven innovation principles and focus on System of System capability by looking at:

What sort of data and information should an open product passport contain that will enable cross-industry applicability and opportunities for new value streams? What is core and priority critical materials across sectors and within products? What data should be public domain v commercially sensitive? What information architectures would facilitate re-use and integrations? What technologies could be used for data capture etc? How would a product passport work in the context of product-service systems and more complex systems comprised of multiple sub-systems and modular components? What policy frameworks, regulations and governance might be needed? How feasible are our proposals and what are the practical considerations?

If you would like to get involved, please get in touch with me via email: m.r.n.king@lboro.ac.uk